|

|

|

2/5/2022 Cull until you cryCull until you cry is an expression that I have heard repeatedly on the Goat Gab podcast. Since I like to be systematic when thinking about my farm, I decided that this was a good time to think through what that means for Owlhaven. This blog will examine selection for herd improvement following a rather winding path:

<

>

Cull until you cryCulling has gotten a bad rap over the years. It is usually associated with slaughtering undesirable animals. However, Nigerian goats have a broad market which includes pet buyers and homesteaders. Entonces, culling can also mean placing goats that do not fit in your program in homes as pets or home milkers. In addition, goats that may not fit your program may be perfect for someone else's program. It is a desirable practice that can help your herd advance and reduce the likelihood of burnout (see my May 27, 2021 blog). This blog will look at my past practices, new practices that I am implementing, and other considerations. Everyone's practices and priorities are different, there is no such thing as one size fits all. As you read the blog, consider what might work for your farm, as is, or with some tweaks. Be businesslike

Find your target marketWhen it comes time to sell, most of us have encountered buyers who are shocked at our prices. This has been reinforced by misinformation on the internet. A very brief search revealed numerous authoritative-looking posts stating that goats should cost between $50-500. One author shared that the sources of these numbers were Hoobly and Craigslist.

That is the wrong market segment for registered goats. Before you can be profitable you have to find the right market segment and get their attention. A great place to start is Facebook groups focused on registered Nigerians. They're easy to find, just do a search. Develop a pricing scheduleDevelop a pricing schedule that is aligned with farms that have similar genetics. Pricing schedules give you a systematic way to increase prices based on the individual doe's accomplishments, such as earning a milk star. Talk to your colleagues about pricing, many have adopted schedules that can help you when valuing your own goats.

Determine your base price *Your base price is what you would charge for a doeling out of a homebred first freshener with no accomplishments to her record, like a junior championship.

At Owlhaven, kid sales must average $725 per doe each year. Purchased does should also make back their purchase price over time. For very expensive does, that may mean that some of the purchase price may need to be carried forward to her retained offspring. Ultimately that means that they may not be the best purchasing decision. Alternatively, the base price for their kids may be higher than for other does. My pricing has to be realistic. Based on experience, I know where I can price my goats and have them move by the end of the year. My prices are somewhat lower than farms that show successfully at the national level or who have bred national winners. But my expenses are also lower. I manage to get to one show a year right now and rarely take more than three animals, so my show ring exposure is very limited. However, when I have made it to shows, my successes and resulting increase in buyer interest have made it well worth the time and expense. The advantage of showing is that you are displaying your goats in front of your local target audience. Then there are passing fads that boost pricing. I usually ride those out, stay focused on my plan, and carefully evaluate those genetics before incorporating them into my herd (see my blog on consistency). I'm a late adopter - in clothes, technology, cars, and goats. It's saved me beaucoup money and heartache. Develop a marketing strategyFinally, you must develop a marketing strategy, monitor your success, and adjust as needed. At a minimum, this usually means a Facebook business page, website, and search engine optimization. *The next tab will dig deeper into developing your base price. The profitable doeOnce you have a pricing model that works for your farm it's time to start tracking individual doe's profitability. There are two obvious criteria: milk sales and kid sales.

Since most Nigerian farms are not dairy farms (e.g., legally authorized to sell milk and/or cheese), and I know little about marketing soaps and lotions, I'm going to focus on kid sales. But first we need to figure out how much it costs to produce a litter. Calculate annual per doe expensesHere are the factors that I consider:

1. Total annual hay expenses 2. Total other feed expenses 3. Total supplement expenses per year 4. Total bioscreening expenses 5. Linear appraisal 6. Milk testing 7. Show expenses 8. Fly control I calculate the total annual expenses for each category because I want my does to cover the expenses of maintaining a small buck herd. As of 2022, Owlhaven's annual per doe expenses are $725. This does not include advertising, utilities, water, vaccines, coccidia prevention, medications, bedding, kidding supplies, emergency vet bills, transportation expenses, AI straws, temporary farm help, or equipment. This also does not include the doe's share in the cost of purchased bucks or the cost of her purchase price if she's not homebred. Track profit or loss over timeThis year I developed a spreadsheet to help me track profit and loss on a per doe basis. I'm also finding that it is very helpful when I get tempted to buy an expensive new animal because it gives me a realistic sense of whether I can make back my money and eventually make a profit off the doe.

The reason that I don't have a buck version is because they are retained or culled based on other criteria. Applying your pricing scheduleI use a spreadsheet to calculate kid pricing based on each doe's accomplishments. Here are the factors that I consider:

Productivity can be measured in terms of milk production and progeny.

Milk ProductionNigerians are first and foremost dairy goats. Which means that pricing and sales are dependent on their ability to produce milk per industry expectations. At a minimum, they must be able to earn a milk star by the age of 2 years. I work full time, so a 305-day lactation is unrealistic for me. My does have to be able to earn their milk stars on One Day Test. First fresheners get a pass where production is concerned. However, I prefer to freshen does as yearlings so that I can start evaluating mammary structure.

If they aren't big enough to breed at 8 months of age, then I'm going to consider selling them, unless I'm considering showing them as dry yearlings. ProgenyIn my blog on consistency, I observed that I've selected animals for linebreeding because of the consistent quality displayed by their progeny. Here are some of the questions that I ask when I'm evaluating mature does.

1. Are her offspring strong milk producers? 2. Have her offspring done well in linear appraisal? 3. Are her litters a desirable size for your program? 4. Does she deliver kids that are generally uniform in size and healthy? 5. Do her progeny move you closer to your goals? 6. Are her progency consistently marketable? A bit more about litter size. Singletons are problematic because they can result in risky kiddings, poor milk production, and reduced kid sales income. Litters in excess of four kids typically result in at least one kid that requires additional support to survive. Linear AppraisalThe doe herd must be structurally sound in all areas for their kids to be marketable. I monitor this - and adjust prices accordingly - using linear appraisal.

First, I screen young does against the most recent median linear trait scores for Nigerians. If they pass the screening, their kid prices go up. If they don't pass the screening, they are sold. Prices also increase for final scores of 90 or above and E mammary systems. Second, I track linear trait and structural data using a spreadsheet that goes back a minimum of three generations. Then I analyze the percent of Es, Vs, Gs (good plus), As, and Fs in the structural data. For the linear traits, I analyze where they score in relation to the current median scores for the breed. This analysis is performed when I am considering new genetics and is updated every time one of my goats is scored. Here's an example: Panache's genetic analysis for rump, shoulder assembly, and front legs. These are the only areas where his genetics have "acceptable" scores. There are no "fair" or "poor" scores. I like displaying the entire range of scores, from excellent to poor because it keeps me from getting lost in the details. I don't like to see pluses and I hate As. I tend to forget how close to VG the GP score is, and I always forget that it's a six-point scale. This chart pulls me back out to the big picture. Panache's structural score analysis (Panache, parents, grandparents, great grandparents)

Time is money, so I also consider what is involved in caring for each goat.

HoovesAt Owlhaven the buck and doe paddocks are a minimum of two acres each. They have plenty of rocky dry lot to roam and wear down their hooves. What I don't have is time, so I can't afford high maintenance animals. Hooves get trimmed a few times a year and visually checked when I'm out in the paddocks. Goats with hooves that don't wear evenly or have other issues don't get to stay. I'm fine with spread toes as long as it isn't excessive. I've learned that spread toes is a regional thing. California has more sandy soil, ergo more goats with spread toes. That was another bit of Goat Gab information.

KiddingParturition can become an expensive medical emergency very quickly, so ease of kidding is one of my selection criteria. Contributing factors include size at kidding and rump width.

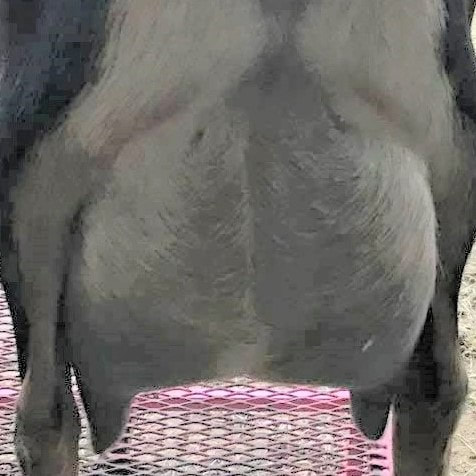

Since I prefer to freshen yearlings, I need doelings to be at least 40 pounds at 8 months. Rump width is something that I've been working on for years. Thanks to Linear Appraisal data, I've made very good progress in this area. I also prefer to retire does once they start experiencing kidding problems. This can become a concern around eight years of age. Teats

Candid pics and videos - lots of them

Incremental cutsThis has been a tough year all around, which means that I've ended up buying back goats from some clients who have had to liquidate. My numbers spiraled up way too high for my comfort. It's not the first time my numbers have gotten too high, and it won't be the last. My strategy is simple, start at the bottom and work my way upwards through all the obvious cuts. Don't slow down until it starts to hurt, then take a break to reflect. See my managing burnout blog for more on this topic. SummaryBefore you make sales decisions, consider having a checklist. For me it would go something like this: 1. Is she profitable? 2. Is she capable of earning a milk star by her second freshening? 3. Did she pass a linear appraisal screening? 4. Did she have conformation or behavior-related problems when kidding? 5. Is she easy to maintain (e.g., hooves, mammary health, weight, ease of milking by hand or machine)? 6. Have you already sold all the animals that fall below her in the rankings? 7. Have you taken lots and lots of candid pictures and videos and analyzed them against the scorecard? 8. Can training or maturity correct any behavior problems? 9. Are her daughters performing as well or better than their dam? Something that I am considering is creating a spreadsheet that ranks the goats in subgroups by kidding year. I don't like to sell via reservations because that puts pressure on me to make fast decisions. I prefer to monitor my kids over the course of a year or two before reducing any kid crop to one or two retained does. One last thought: A new insight from Goat Gab was the idea of not being so focused on dam lines that you retain an animal that you would have otherwise sold, just to preserve her dam line. Zoom out your focus to consistency within your whole herd. If she doesn't make the cut, sell her. Comments are closed.

|

|

|